There are four rules to understand when building products out of open source software. A product team (engineering, product management, marketing) needs to understand these rules to participate best in an open source project community and deliver products and services to their customers at the same time. These four rules are the start of all other discussions about the open source product space.

Rule #1: You ALWAYS get more than you give

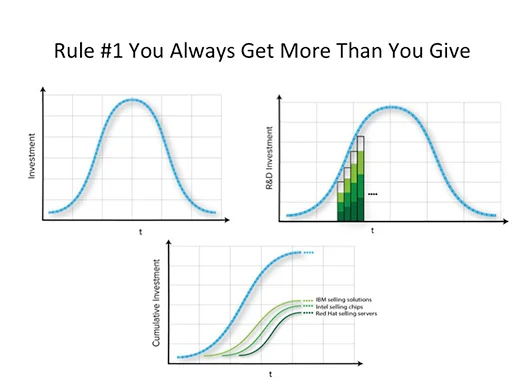

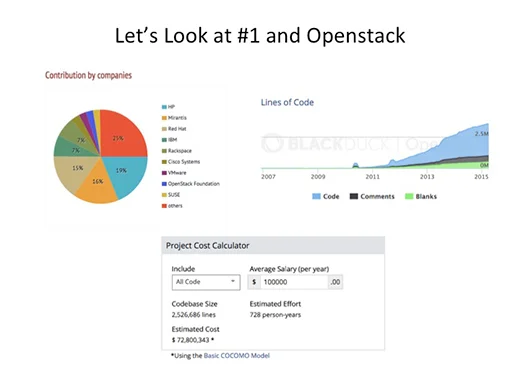

The investment over time in a technology follows a normal distribution. Think about the investment in open source projects as a stacked bar chart where company and individual contributions are taken together and replace a single company’s investment. So the collected investment looks the same in an open source project as a single company’s investment looks when developing closed proprietary software products. Individuals and companies contribute to meet their own selfish needs. It’s a perfect asymmetric relationship where the contributor gives up some thing relatively small in value (their contributions) and gets something substantial in return (an entire working piece of software). One can look at Openstack or the Linux kernel to see this activity best in well measured ways. Instead of viewing this as giving away IP, it needs to be looked at rightly as gaining all the rest of the IP.

Lines-of-code and the COCOMO calculations come from Openhub.net crawling repositories. I understand exactly how fraught lines-of-code is. I understand the concerns over the accuracy of COCOMO, but they are representative models if not perfect ones, and they show the trends appropriately.

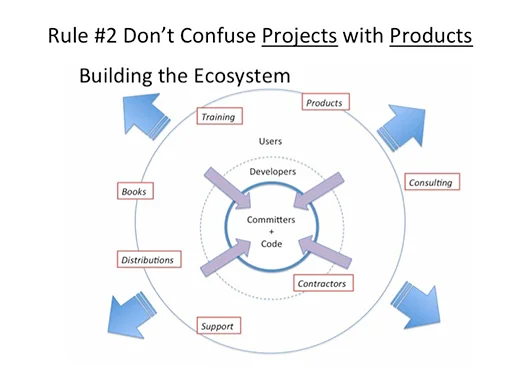

Rule #2: Don’t confuse projects with products

This one is sometimes hard to understand. First, we need to assume we’re talking about a well-run, successful open source project. (More on this in rules #3 and #4.) A project is a collection of working software that installs and runs and solves an interesting problem. It’s a collaboration and conversation in code between a relatively small number of people developing the software that have write access on the software repositories (i.e. committers) and hopefully a larger set of users and contributors. A product is something that solves a customer’s problem for money.

Projects are NOT products. While a lot of excellent software can come out of a well-run open source project that relieves some of the work for engineering (see Rule #1), there is enormous work still to be done to turn it into a problem-solving product for customers. The Linux kernel is a project. Fedora is a distro project. RHEL is a product. “But what about Ubuntu,” you cry? It’s a variation on the business model. Ubuntu is a distro project. The Long Term Support (LTS) editions are the basis of multiple products for Canonical.

Products meet customer expectations of value for money. They install out of the box, run, and come with warranties and indemnifications, services (support, upgrades, training, consulting), and documentation. The product may be a service or hardware wrapped around the project. Products are as varied as markets of problems customers want solved for money. While good projects tick the first two boxes (install, run), they don’t tackle the customer focus the same way. Projects also solve much narrower problems than customers want solved.

And don’t be confused about which open source licenses are involved and whether they’re “business friendly” or not. Different vendors use different strategies around different licenses. There are success stories and failures around every major OSI approved license. The license is irrelevant in comparison to business execution.

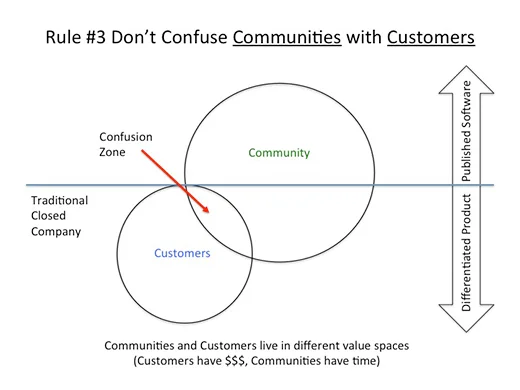

Rule #3: Don’t confuse communities with customers

This rule is tightly woven together with Rule #2, and if anything harder to understand. If Rule #2 is about engineering and business model, Rule #3 is about messaging and sales. Communities and customers live in different value spaces. Communities have time, but no money. Customers have money, but no time. Perhaps a better statement is that customers spend money to expedite a solution and remove risk, while communities (individuals in community) have no money.

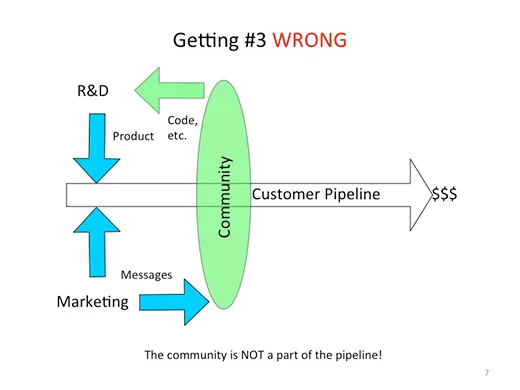

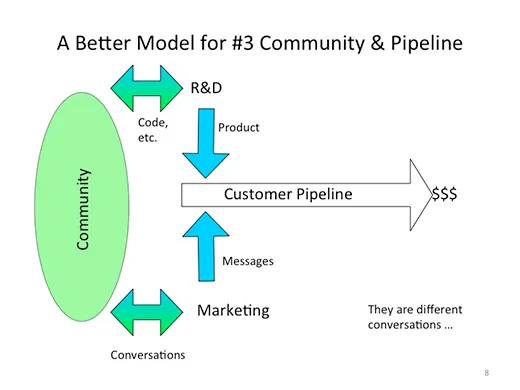

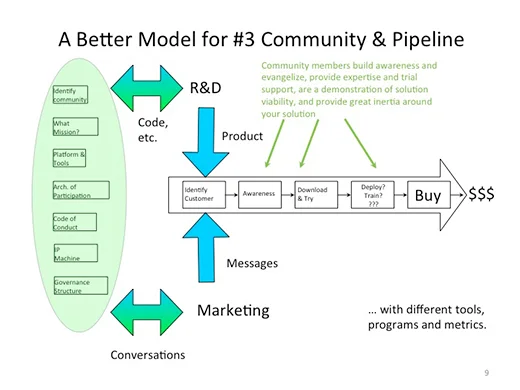

Traditionally, engineering feeds products into the pipeline, marketing feeds messages, and sales pulls qualified leads through into closed deals. A simple matter of execution. Many many companies using open source think that the project community is a part of this pipeline, and they further believe this when they find customers in community forums. They may even think the community project is a try-before-you-buy. All of this is WRONG.

The conversations that a company (product management, engineering, marketing) has with its relevant communities and conversations with paying customers are different conversations. Each conversation has specific tools and rules of engagement. Successful companies understand how to have these conversations. There are well understood tools for building and qualifying pipelines. There are equally well understood tools and rules for developing successful communities (Rule #4). Each tool chain and conversation has different metrics to capture and consider.

There IS interaction between a company’s community and customers. Community members are evangelists for the project (so there’s value to link it to the company brand in thoughtful ways). Community members provide support and expertise to potential customers that are self-qualifying in the project community before re-joining the product pipeline. Community also provides inertia for the ultimate product solution by being a sink for expertise and time invested. The challenge is to keep things crisply separate between the community and customers such that you can quickly and easily recognize what role the person in front of you is playing and guide them appropriately. There must never be confusion in the messages (deliberate or otherwise).

For example, the product is for customers. If you have a trial edition, as in try-before-you-buy, then the “buy” word is there, so, customer conversation. If you have a community edition, then build a community (Rule #4), because otherwise you’re simply publishing software under an open source license without gaining any of the benefits of an open source community. These are separate things, which brings us to the final rule.

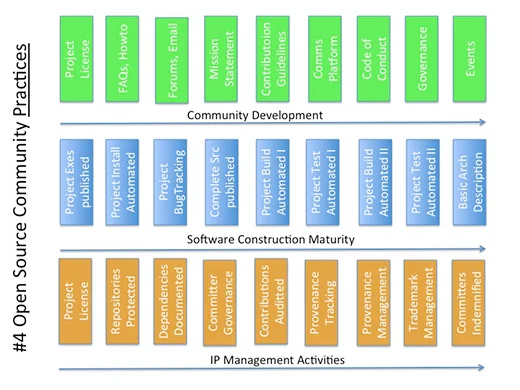

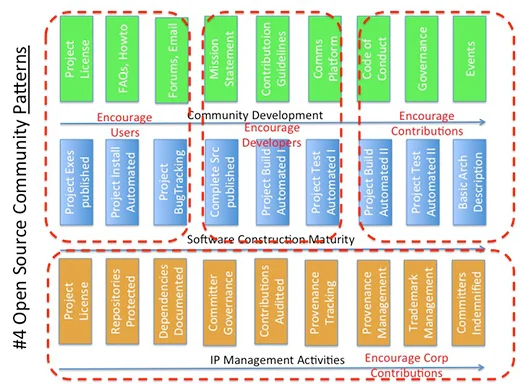

Rule #4: Successful open source project communities follow well-understood patterns and practices

All successful open source community projects follow the same set of patterns and practices. The project starts as a conversation in code around a small core of developers. There are three on-ramps that need to be built. First drive use and grow the user base, because that will lead to developers finding your project. (You NEED freeloaders! It means you’re doing it right.) The software has to be easy to install and run. Users will tell you what they need, i.e. you get bug reports and feature requests in return for getting this right. More importantly, developers find you.

Second, make it blindingly easy to build the software into a known, tested state. This will allow developers to self-select and experiment for their own needs. Assuming a smart developer will figure it out is throwing away developer-cycles. They won’t. No one wants to waste their time on your laziness and lack of discipline. They’ll leave in frustration and disgust. Getting them back will be very hard if not impossible. Get this right and you’ll get the next set of harder bug reports and likely suggested fixes.

Third and last, tell developers how and where to contribute and make it easy to do. Thank them for the contributions. If things other than code are to be encouraged, set up those contribution channels as clearly and make them easy. Regularly say “thank you.” Reward folks anyway you can, especially when you’re a company.

Building communities is hard work. It doesn’t come for free. It does, however, bring value with it in terms of contributions from users and developers, as well as stickiness for the technology.

The last collection of practices in this space is around understanding the role of foundations and open source software. Foundations organize and clarify IP management regimes. Foundations can do many other things, but if they don’t get this central thing right, then they’re a failure for the project community’s potential for growth. Clarifying neutral IP ownership allows growth for dedicated investment from participants and contributors interested in growing the entire ecosystem, i.e. companies trying to solve problems for customers.

Foundations create neutral space in which companies can participate on equal footing. A company building products out of open source projects they didn’t start and own (e.g. SUSE and Linux, HP and Openstack, etc.) need to understand clearly how their contributions are handled and that they aren’t simply building someone else’s product. Likewise, a company that has started an open source project and wants to drive adoption and growth of an ecosystem around it would do well to contribute the project software IP to a separate non-profit foundation (or create one if appropriate) such as what Google is presently doing with Kubernetes, or Pivotal has done with Cloud Foundry. This is ultimately a fourth on-ramp to get right.

Conclusion

So there you have it. Everything I’ve learned over 20 years of open source project support, foundation participation, and product engineering summarized in four rules, 10 slides, and approximately 1,600 words. I look forward to questions and comments.

—

Source: https://opensource.com/